Connector Series - Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics, supply and demand

The global economy and the ability to move containerised cargo around the world has been in turmoil for more than two years now. While the global pandemic per se has undoubtedly been at the centre of the impact we have seen and experienced in shipping, other major disruptive events have made the situation even more complex.

Still worth mentioning in context of the pandemic are the different Covid-19 responses that have been taken worldwide. While in many parts of the world countries seem to have taken the approach to adapt and live with the virus, China for example has continued to apply a zero Covid-19 strategy. The result of that could be seen in the lockdown of cities like Shanghai that led to unprecedented congestion of ports, dysfunctional feeder connections and a backlog of more than a quarter of a million TEU which, when Shanghai opened again, flooded the trade lanes in a massive wave of containers. For example, on the East-West trade lane this resulted in cargo ex New Zealand to Europe only making its connections after a substantial delay of several weeks since the higher paying cargo from China was prioritized in an environment of limited capacity.

The world has also seen a war breaking out in the heart of Europe. The conflict in Ukraine, starting in February 2022, suddenly triggered a catastrophic and costly humanitarian crisis, with substantial economic damage. The consequence of the war and its geopolitical interdependencies has affected the oil price substantially. Since the start of the war, it has seen steep rises, increasing the cost of production and transport. Increased prices for oil could also be felt at the consumer level when filling up their car at the pump. Fuel, but also food prices, have increased rapidly, which defines the third major macroeconomic factor that has a massive impact on global economies and trade: inflation.

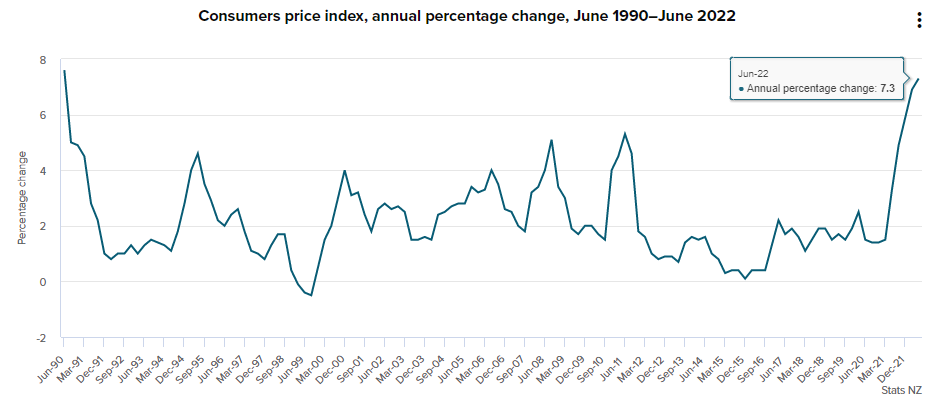

With inflation in New Zealand, currently sitting at 7.3% and as such at the highest rate for 30 years, worldwide consumers experience similar if not worse pressure. And the fear that inflation combined with limited growth will spark recessions is high, which is why central banks around the world have moved swiftly and with force to introduce comprehensive fiscal countermeasures in a complicated attempt to contain price pressure and safeguard growth.

These three main factors: 1) global pandemic along with ongoing uncertainties around the further development, 2) a war in Europe along with dangerous geopolitical tensions and a risk of further escalation as well as 3) inflation with risk of recessions, can in their combination be referred to as a comprehensive and complex “multi-factor-crisis”. And this multi-factor-crisis is the background and context of the world economy in its current state and outlook, consequently affecting world trade with a strong impact on container shipping as an integral part of world trade. Together, they contribute to a significant slowdown in global growth in 2022 so far and a grim outlook.

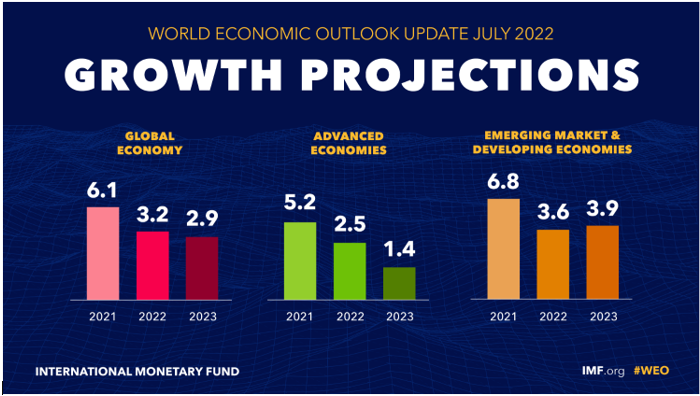

After its severe collapse in 2020 and a negative growth (-3.3%) due to the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, the global economy was on a difficult and long but steady path of recovery to grow by 6.1% in 2021, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The surge in demand for goods over services in a world still dominated by the pandemic with very limited travel and re-occurring lockdowns, resulted in extraordinary volumes and historically high freight rates for containers shipped across largely disrupted supply chains.

But in the context of the multi-factor crisis, in its latest World Economic Outlook (July 2022), the IMF paints a bleak picture of the global economy. The latest growth expectations for 2022 are 3.2%, which is a further downgrade from the IMF’s April assessment of 3.6%. That had already been taken down from 4.4%, published in January, which again was a downward correction from October 2021, where the growth was projected to be 4.9%. Also, the projections for 2023 have been downgraded further, to an estimated growth of now only 2.9%. While the so far expected softer demand for goods derived in part from a shift from spending on goods back to services, like travel when borders opened up again, many consumers feeling the pressure of inflation and a cost-of-living crisis now cannot spend their money on either of them.

The impact of the crisis drivers on the consumer is immense and with the extreme uncertainties around the way forward, IMF describes the demand outlook as “Gloomy and more uncertain” as well as the risks to the outlook as “overwhelmingly tilted to the downside”.

According to Drewry’s latest Container Forecaster, the economic growth projections translate into estimated global TEU growth figures of 2.1% for 2022, after 6.1% in 2021. The projected growth for 2023 is 3.5%. In this context it is noteworthy that Drewry underlined that “[…] To say that forecasting container demand has become more arduous is a gross understatement. A plethora of events and trends (some of which are conflicting) are having a domino-like negative compounding effect across various markets, with differing impacts on countries and regions. Their varied response, in turn, have differing consequences on container demand.” It is also noteworthy that Drewry’s estimates are based on the April outlook, and it can be assumed that in their next container demand forecast they will follow IMF’s new guidance.

With regards to the supply side, the World Container Fleet has never been larger and currently sits at about 25 million TEU. And it is set to grow at speed: While in 2021 vessels with a combined capacity of 4.7 million TEU were ordered, the placement of newbuild orders in 2022 continued strongly, with approx. 1.7 million TEU capacity ordered in the first half. The total orderbook of close to 30% is at the highest ratio of the existing fleet in the past 10 years:

At the same time, scrapping has been at the lowest possible level in 2022, with not one single ship being sent to the breakers so far. Everything that floats and can carry containers, is being bought by container lines instead of scrapping yards and deployed in a market in which returns even on far overprized second-hand tonnage are just too good as to not use the ship just a little bit longer.

But even though nearly every possible vessel is on the water, space is tight, and rates are high. This is due to mainly two factors: Ongoing global port congestion and very tight capacity management.

Congestion has been the major disruptive factor since the pandemic started. The reasons for it are various and interconnected, ranging from labour shortage in the ports to physically work the vessels, via terminals and warehouses bursting at the seams to hinterland bottlenecks with a lack of truck drivers or clogged rail connections – not to mention lockdowns of whole cities, like the example of Shanghai. Several dozens of ships waiting outside ports for days if not weeks have become a familiar picture. And congestion has constantly worsened over time. Drewry’s Port Congestion Z-score indicator, showing the average number of ships waiting outside selected ports compared to 2019, even shows that in 2022 the situation has become worse than ever:

In terms of tight capacity management, the lines are optimising their profit streams with rigor. Ships are deployed wherever possible in the trades with the highest contribution levels and equipment is steered towards those trades. New Zealand, unfortunately, is not one of those trades and as such suffering constantly. Also, despite zero scrapping, carriers manage the capacity in their trades closely, for example with extra slow steaming or blank sailings. The development of the idle fleet is another good indicator for that. It is clearly visible that the lines have started to react on softening demand with idling a part of the deployed fleet:

While in the past many carriers were driven by market share, today maintaining profitability on the highest possible level has clearly become the focus of their attention.

Next Chapter